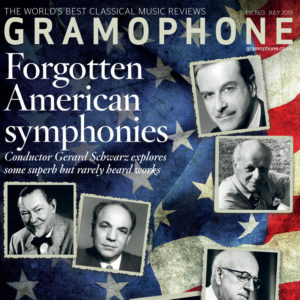

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – August 2019

This month’s cover feature has prompted some age old cravings in me. I have travelled far and wide in the United States, I have repeatedly given my regards to Broadway, the American Songbook is as much a part of me as anything emanating from our own green and pleasant land, and when I hear even a few bars of Copland’s Third Symphony or indeed the Third symphonies of Roy Harris or William Schuman there is an inescapable identification which suggests that at least a part of me, emotionally speaking, resides in ‘the land of the free’. For me that phrase has always more readily evoked a state of mind than it has a social condition. The open road seems to beckon from every bar of what might generically call ‘the great American symphony’.

This month’s cover feature has prompted some age old cravings in me. I have travelled far and wide in the United States, I have repeatedly given my regards to Broadway, the American Songbook is as much a part of me as anything emanating from our own green and pleasant land, and when I hear even a few bars of Copland’s Third Symphony or indeed the Third symphonies of Roy Harris or William Schuman there is an inescapable identification which suggests that at least a part of me, emotionally speaking, resides in ‘the land of the free’. For me that phrase has always more readily evoked a state of mind than it has a social condition. The open road seems to beckon from every bar of what might generically call ‘the great American symphony’.

In his cover feature Gerard Schwarz – a great advocate for its cause – has singled out his favourites, many of them mine, too. I would most certainly add Bernstein’s Second Symphony ‘Age of Anxiety’ – an urban voyage of self-discovery. But perhaps there’s a different perspective from an ‘outsider’ like me as to what it is in the form and tone of the music that encapsulates both the physical landscape and emotional aesthetic of America. The wide spacing of orchestral lines in the opening pages of Copland’s Third, the bracing open fifths, the pioneering resilience and resolve of all those imperative rhythms and kick-ass syncopations – like the final Toccata of Schuman’s Third turbo-driven by the crack of jazzy side drum rim-shots – and most of all the ‘aspiration’ which rings out in the jubilant horns of Harris’ Third or Copland’s Fanfare for The Common Man or the brave new dawn, at the close of Bernstein’s Second.

Schwarz also mentions Charles Ives – how could he not – but he says ‘though respected as an innovator (he) was less successful as a symphonist, though some may disagree.’ I disagree. Respectfully but vehemently I would assert that the Fourth Symphony could easily lay claim to being not just the most important American symphony but the most important single piece of American music, period. The first and last symphonic masterpiece by an American composer.

As someone who carried the American Transcendentalist tradition forward from literature through music into the next generations Ives was bound to ask the ‘meaning of life’ question. There is a hymn underscoring it – ‘Nearer, My God, to Thee’ – the last thing heard as the Titanic went down. It is the beginning and end of the Ives Fourth. And in between there is the ‘Comedy’ of life – namely Ives’ stupendous second movement – where all life is quite literally ‘here’, and most of its tunes, too, colliding in cosmic confusion. Imagine Ives thinking ‘is it my fault that a conductor has only two hands?’

But for me the simple fugue of the third movement might be the most radical music in the piece. There is a moment towards its close where a solo clarinet divines its own awkward harmonic counterpoint. It moves me more than I can say.

And when ‘Nearer, My God, to Thee’ returns at the close of the symphony, it’s sung in a modal rather than a diatonic cadence, a change which Michael Tilson Thomas once pointed out to me brings it into concord with ancient music, with Asian music, with all the musical traditions of the world. An American in…well, everywhere.

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE Review: Santtu conducts Mahler Symphony No. 2 ‘Resurrection’ – Philharmonia Orchestra/Santtu-Matias Rouvali

15/12/2023

GRAMOPHONE: André Previn – A Tribute

24/04/2019