A View from the Bridge, Young Vic

These days it almost goes without saying that something extraordinary is happening at the Young Vic. There hasn’t been a show I have seen there over the last two years that didn’t challenge and excite my theatrical imagination. But Ivo van Hove’s staging of Arthur Miller’s A View from the Bridge is something else. It takes such risks and with such audacity – sometimes to the point sensorial irritation – that it’s hard to think of a precedent in stagings of this writer’s work. Removing Miller’s characters from their natural habitat, from their physical time and space, is always risky but placing them in a sterile environment the better to forensically examine their motivations, their passions, demands more of the actors and more of us than you could possibly imagine. It repays in equal measure.

Van Hove takes his cue from from a remark Miller himself made about the Greek drama unfolding everyday on the waterfront under the Brooklyn Bridge. And just as he gave this particular Greek tragedy a Greek Chorus of its own – the lawyer narrator Alfieri (excellent Michael Gould) – his words elevating small lives to lofty heights and rendering in coarse words a poetic gravitas, so van Hove casts each of us as proactive “spectators” in his lecture-cum-amphitheatre slowly (and literally) lifting the lid on a black box of secrets (Design and Light Jan Versweyveld). Two longshoremen showering portends a final image of mythological – you might even say biblical – retribution. It will rain blood.

The acting area is, like the characters emotions, naked – no props, no furniture, no sense of place, one door in and out of the arena. And the shutter on that will come crashing down, cutting off the one escape route. There is no way out. Van Hove’s actors can bear such scrutiny – they are marvellous without exception – ordinary souls with dreams big and small and a human fallibility that is off the chart. At the centre of it all is Mark Strong’s terrific Eddie Carbone whose work ethic, protective instincts, and pride are so all-consuming as to blind him to his obsessiveness. When his exasperated wife Beatrice (an impassioned Nicola Walker) dares suggest that his protectiveness towards his niece Catherine (a feisty and then some Phoebe Fox) has grown into an unhealthy obsession, the hurt and bewilderment and sense of betrayal that Strong projects is devastating.

And all of this is underpinned by a continuous – and I mean continuous – soundtrack of religious choral music, a continuous looping of “white noise” which eats its way into our subconsciousness like a kind of static pulse. Incredibly risky, initially even intrusive (that overbearing Italian Catholic guilt), but eventually the musical equivalent of background traffic roaring over the Brooklyn Bridge.

You will, I promise, never forget the final image of collective tragedy – a scrum of wounded humanity, as co-dependent as it is precarious.

You May Also Like

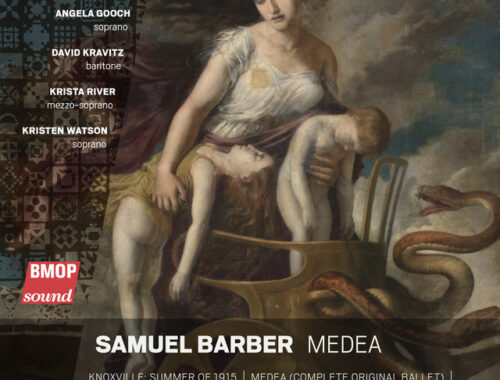

GRAMOPHONE Review: Barber A Hand of Bridge, Knoxville: Summer of 1915, Medea – Soloists, Boston Modern Orchestra Project/Rose

15/09/2021

GRAMOPHONE Review: Mahler Symphony No. 2 ‘Resurrection’ – Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/Daniele Gatti

03/01/2018